Wall Art Exhibitions

New Work

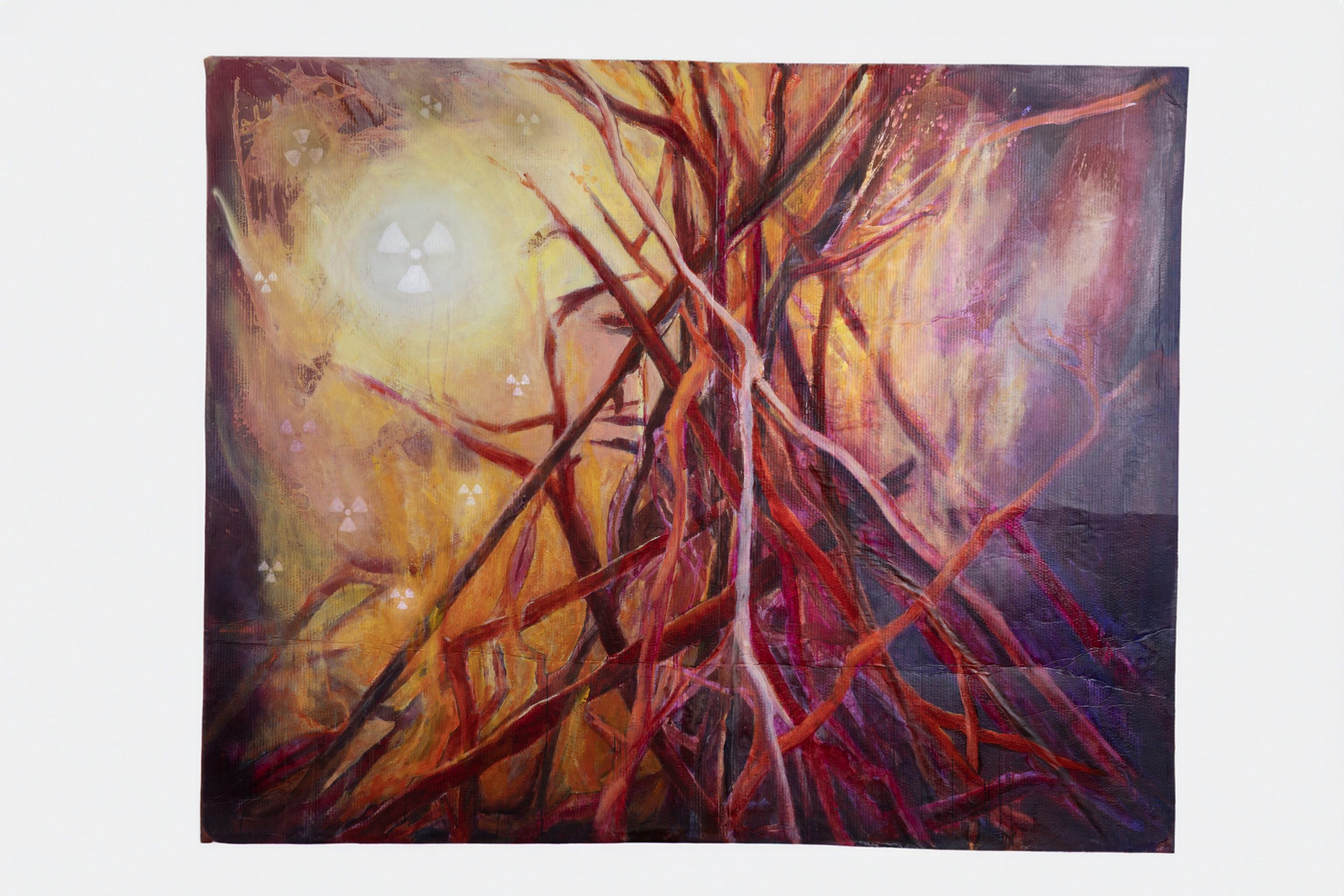

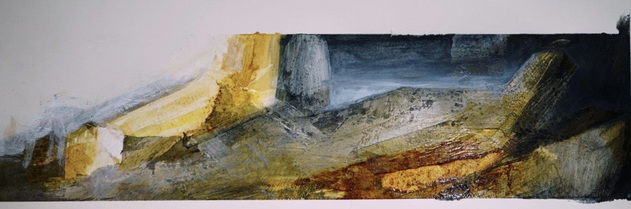

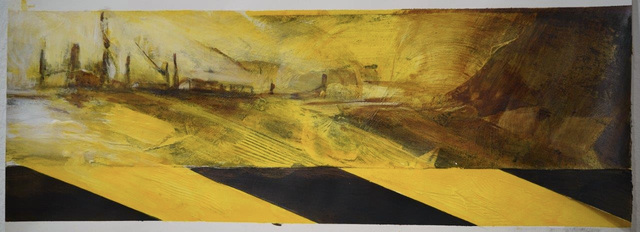

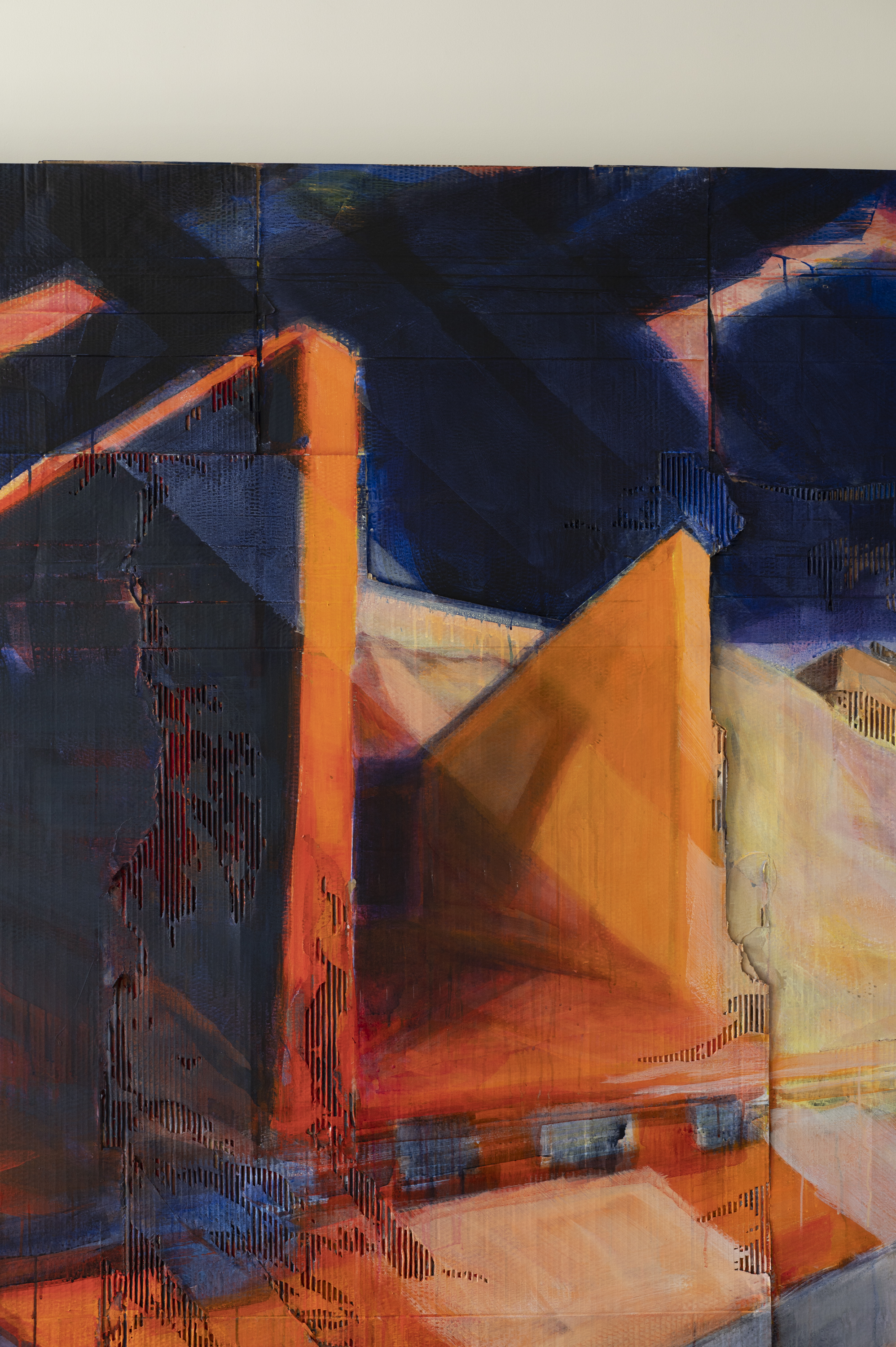

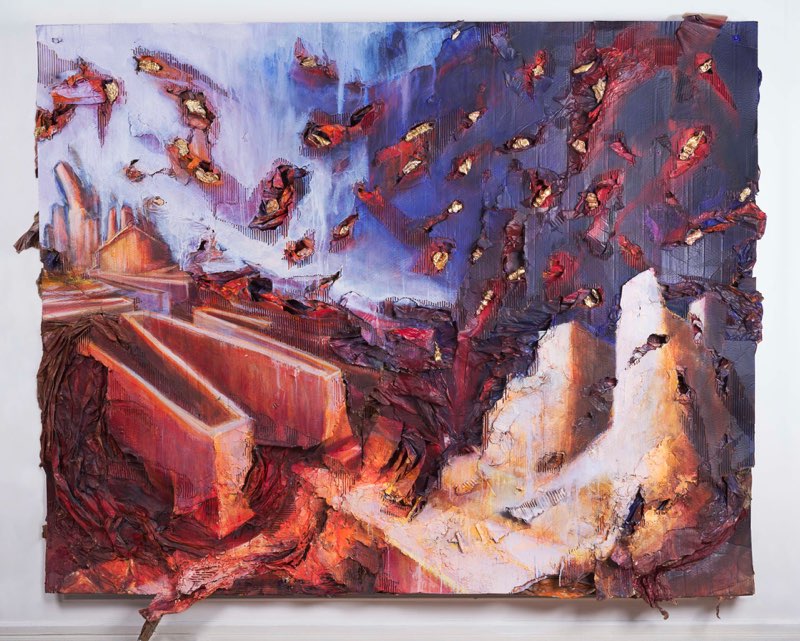

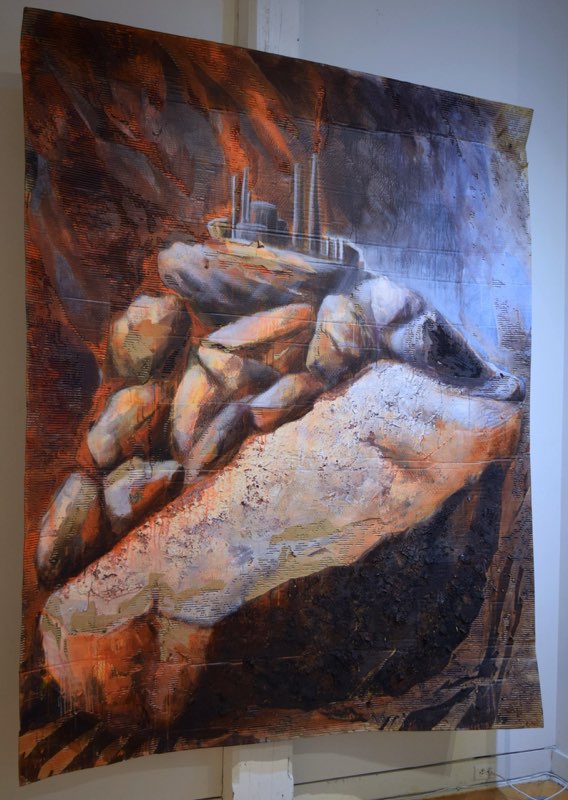

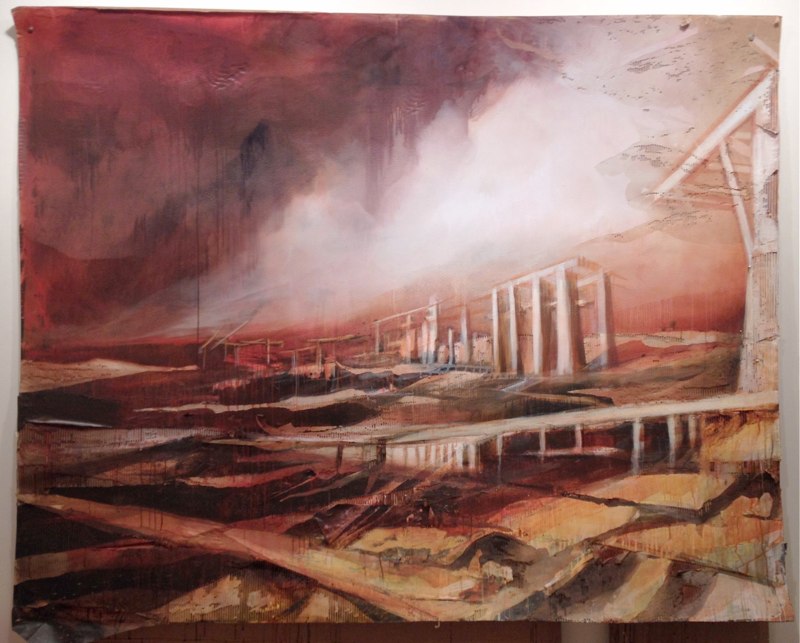

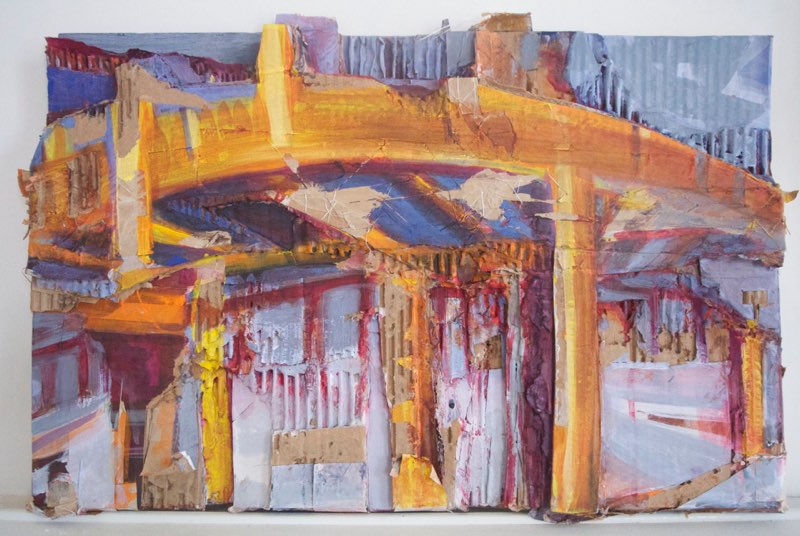

Danger Zone Paintings

Where is violence, there is always a trace. Where there is conflict, there is a memory that serves as a reference for resolution in the future. With the series of “Danger Zones,” I imagine our future self throughout past and present histories of human tectonic activities and their

metabolic regimes.

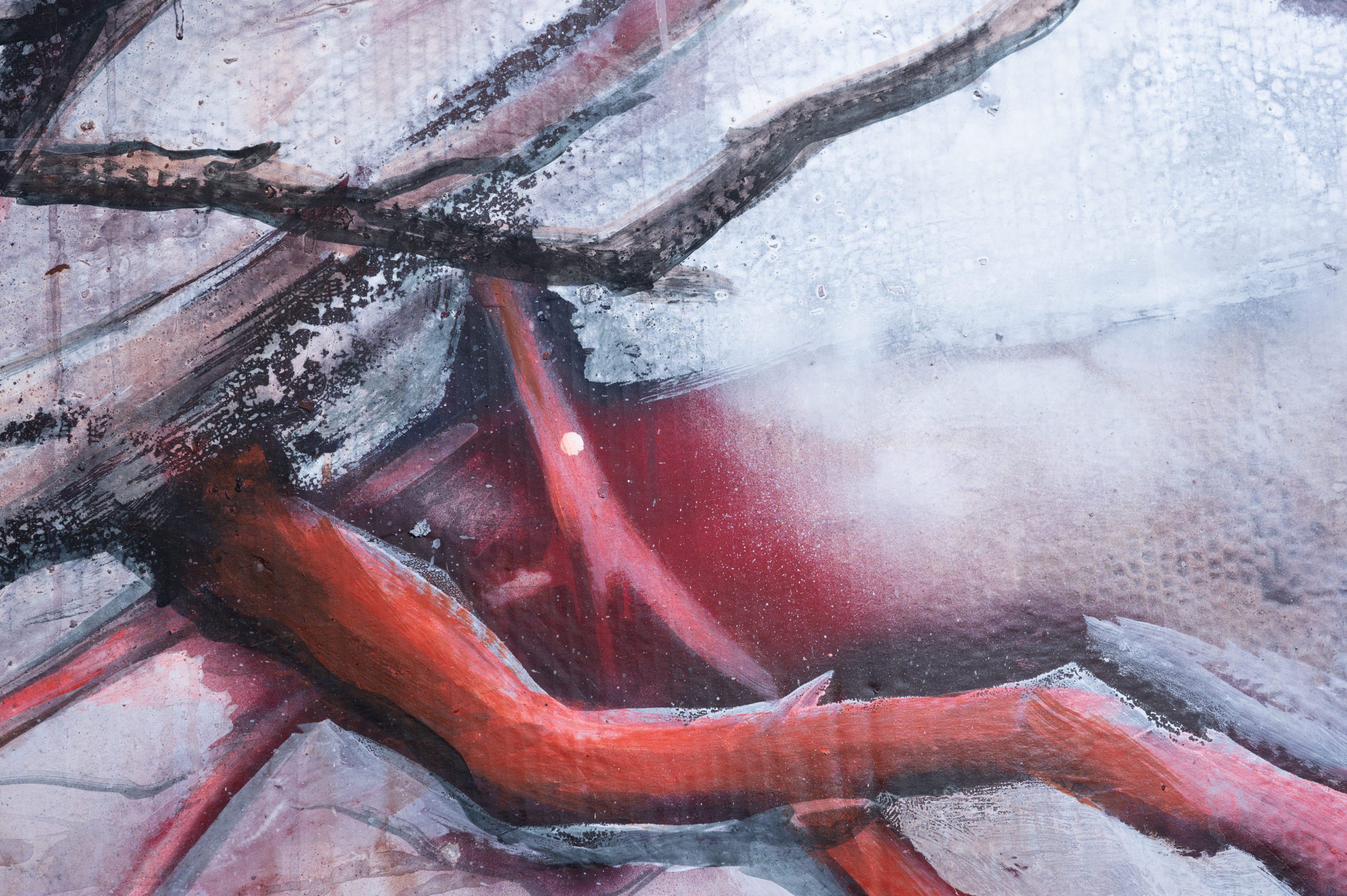

I am exploring future landscapes that derive from present and past unresolved conflicts against nature and each other. Incapable of peace amongst each other and with nature, human activities affect the Earth’s critical zone through exploitation, exhaust, and extinction for all living beings. Derived from my drawing series of Mono-Pol-Lithic, “Danger Zones” refers to geological forces and powerful agencies that emerge from deep time and are revealed in tectonic structures of human activities, transforming the planet into a precarious critical zone for all Earthbounders.

As humankind has already created dispositions of its termination, what kind of marker, landmarks, or engineering are we going to develop to ensure endangered sites remain undisturbed to keep future species safe? What languages will future generations speak to communicate the mistakes we have created in the past-present? What structures and communication systems need to be considered now that could stand for thousands of years to warn future generations of the unstable by-products of nuclear, chemical, and biological forces and ignored consequences?

In my works, shaped environments seem familiar yet come from another time. The images are witnesses from the future and talk about changes in our time while our actions took place in the past. They represent the energy of human activity, which raises questions on how our will to shape the world will behave at the moment.

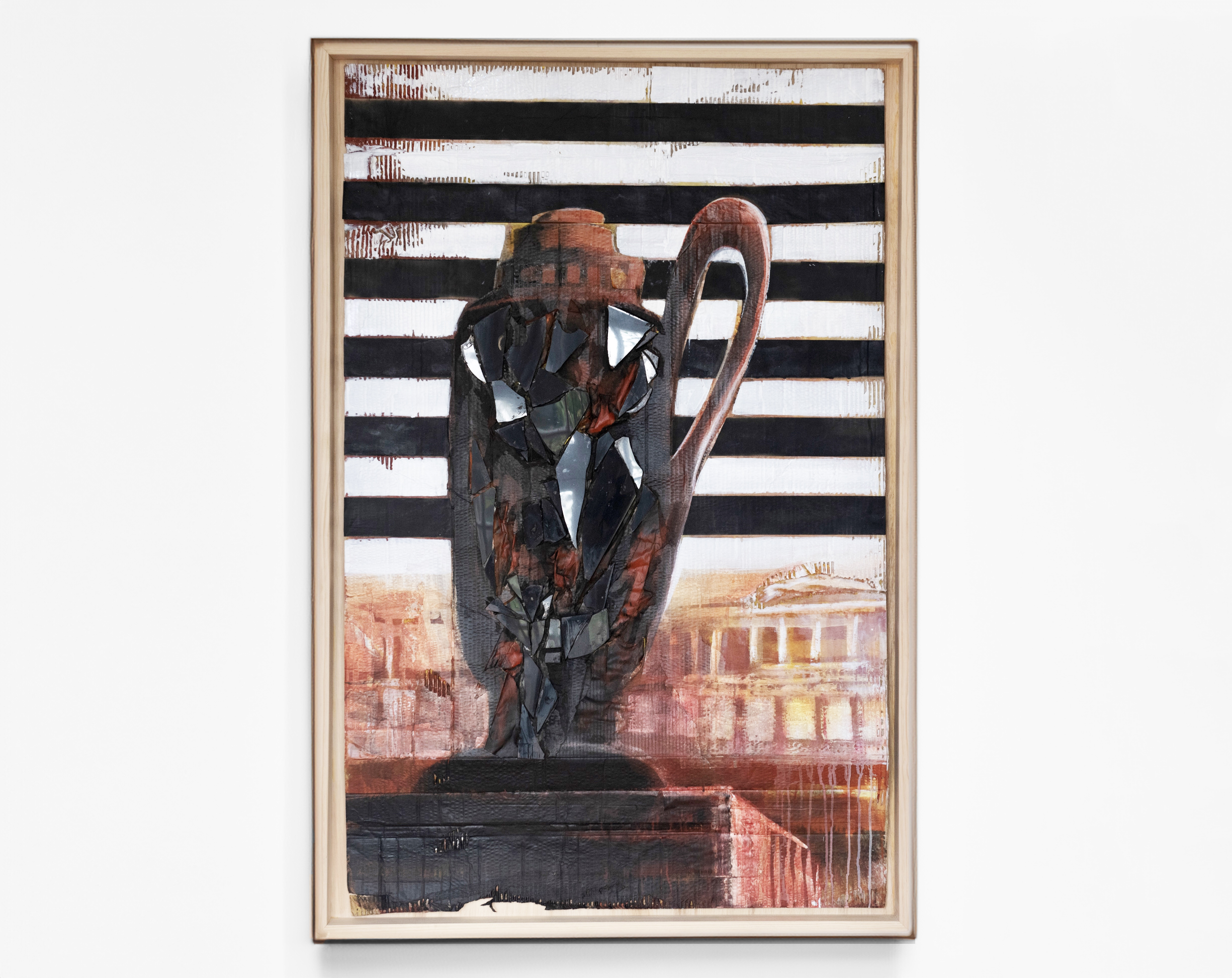

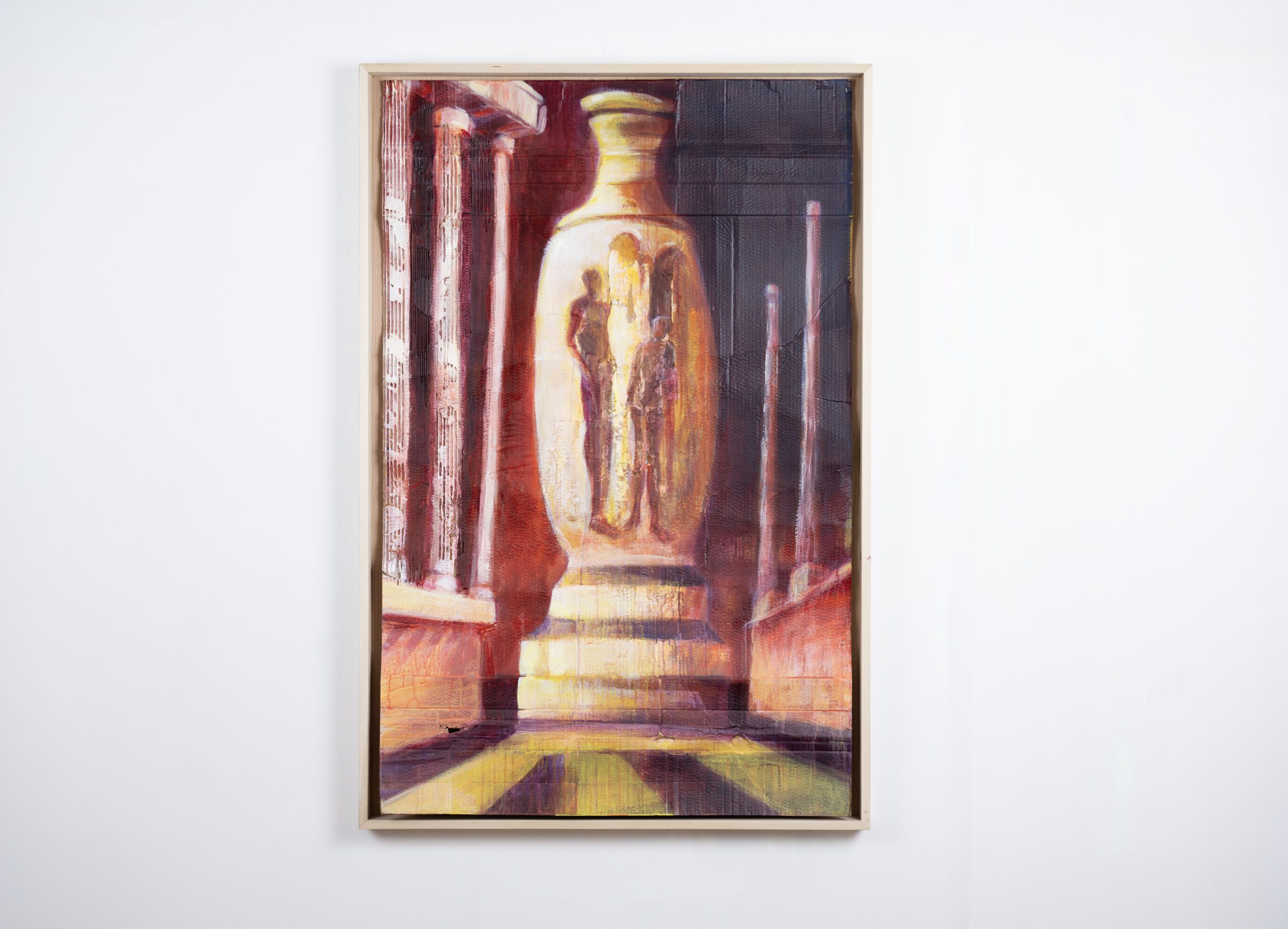

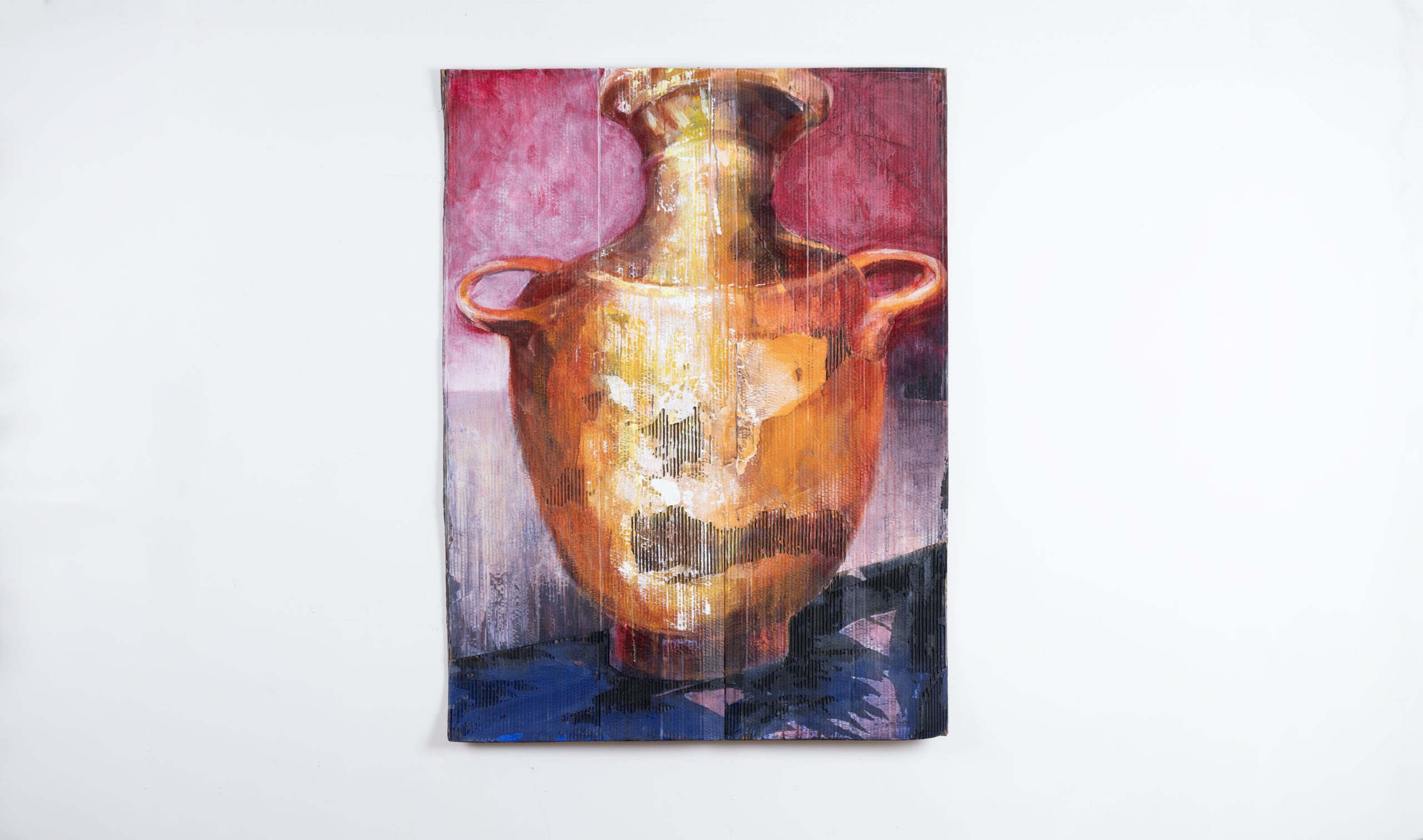

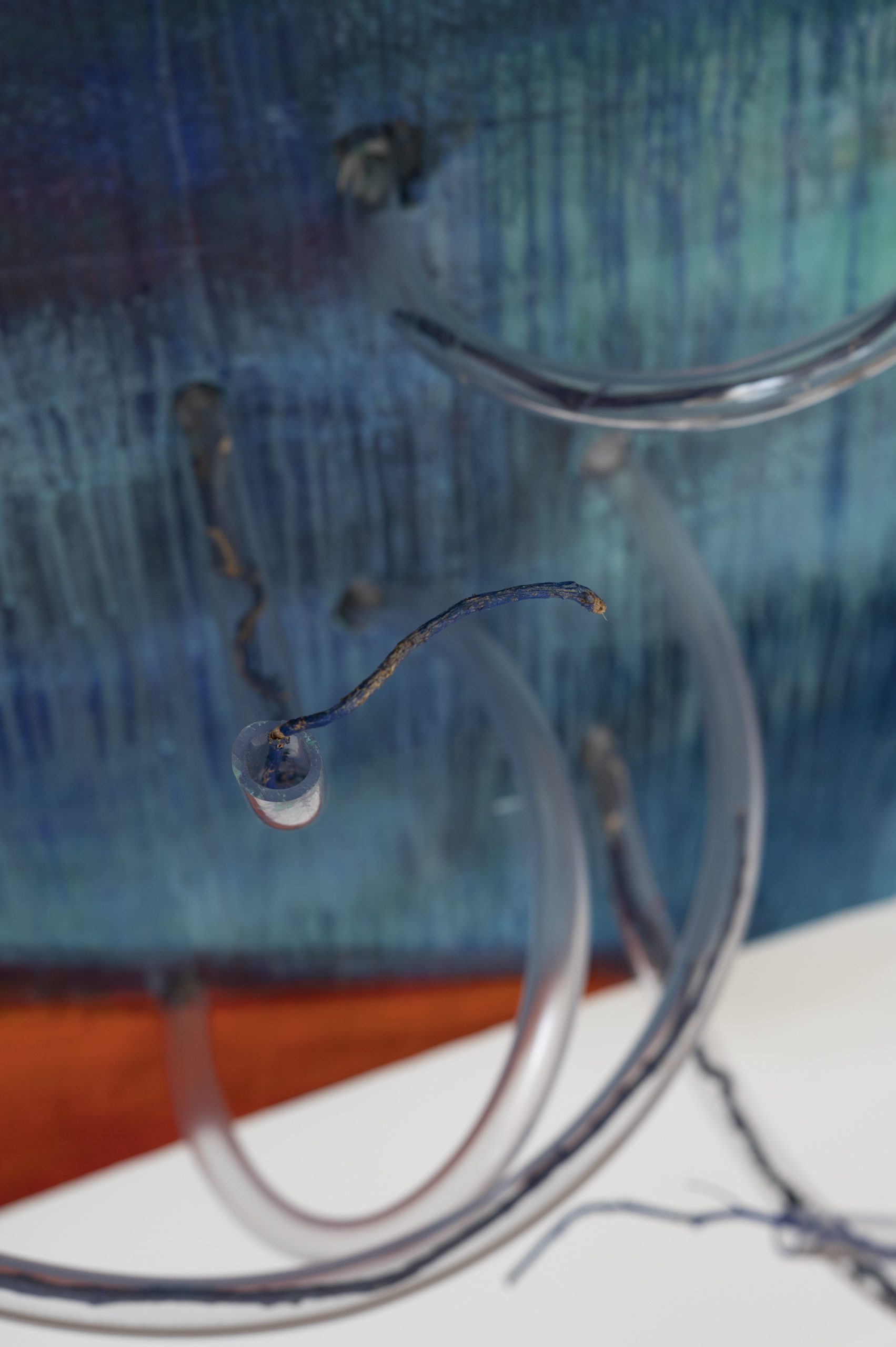

Lekythos Series

My new series, “Lekythoi,” reference ancient greek funeral practices when the ashes of the deceased have been burnt together with the raw clay and through the burning fused as one entity. With my ongoing series of “Lekythoi,” I explore forms of mourning in times of the pandemic dealing with loss and sorrow. Throughout this memory project, I collect, recollect, recycle, and fuse materials of our everyday life that also reflect on the natural world under current conditions of the environment’s exploitation and abuse of life forms and existence on Earth as terminated and fleeting cycles of nature. With applied digital projections, I explore ancient philosophy embedding the past into our present memories and forms of memorials. The digital projection of water invokes the early natural philosophy of Thales (Metaph. 983 b21-22). Aristotle referred to Thales that water is nature, the archê, the originating principle, the basis of all matter, a single material substance. Also, Heraclitus’s (530-470 BC) philosophy informs the concept of universal flux: Nature flows ever onwards like a river. Even the nature of the flow changes – and so do you. Heraclitus’ vision of life is evident in his epigram on the river of flux: ‘We both step and do not step in the same rivers. We are and are not’ (B49a).

Mono-Pol-Lithic Paintings

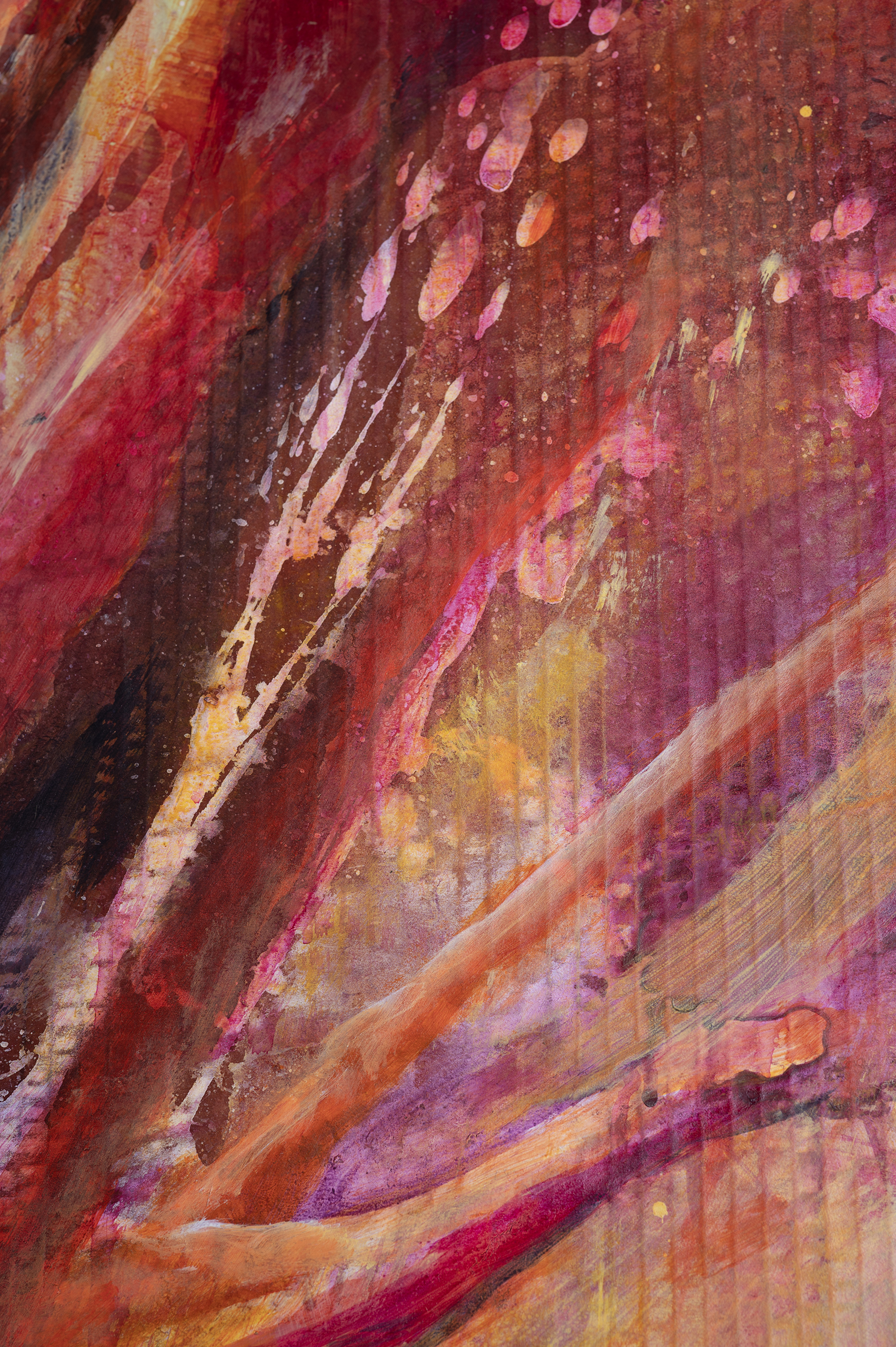

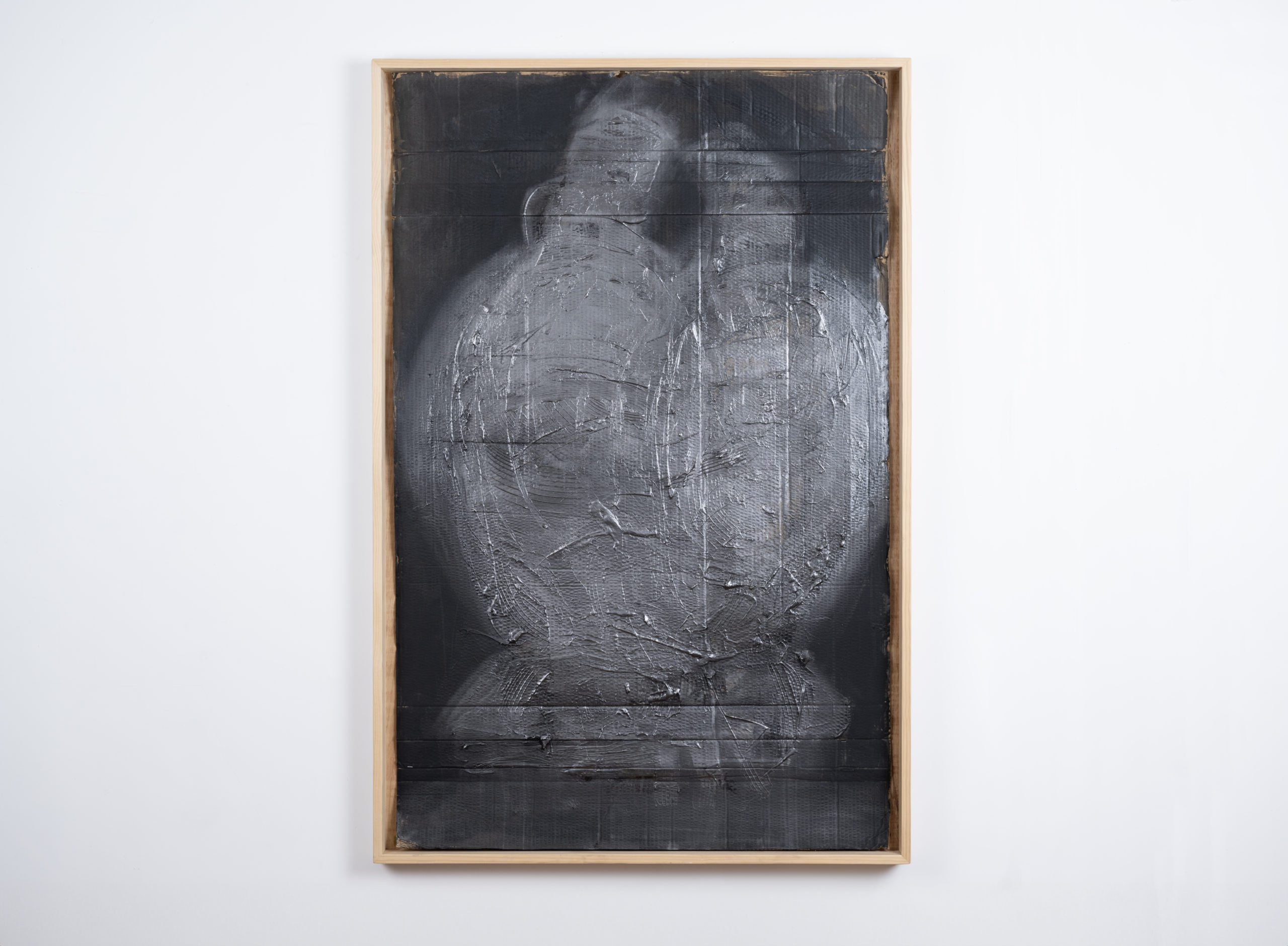

Mono-Pol-Lithic, a new body of work in 2020, refers to monolithic structures, accumulations of tectonic bodies in connection with deep geological time, histories, and myths. I am interested in how political agencies have transformed and depleted the landscape, the actual, political, and societal, and what kind of manifestations of architecture and power structures are revealed.

I want to question how references between deep time and its monumental structures are expressed today.

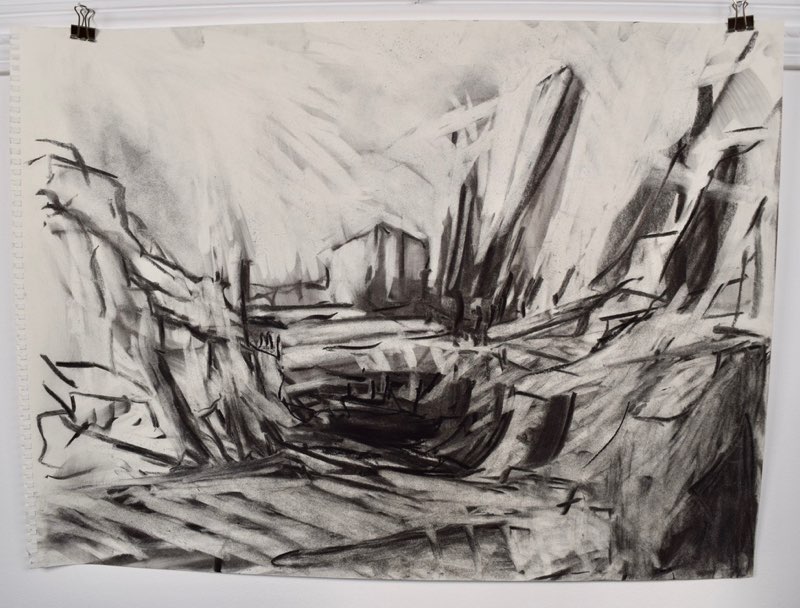

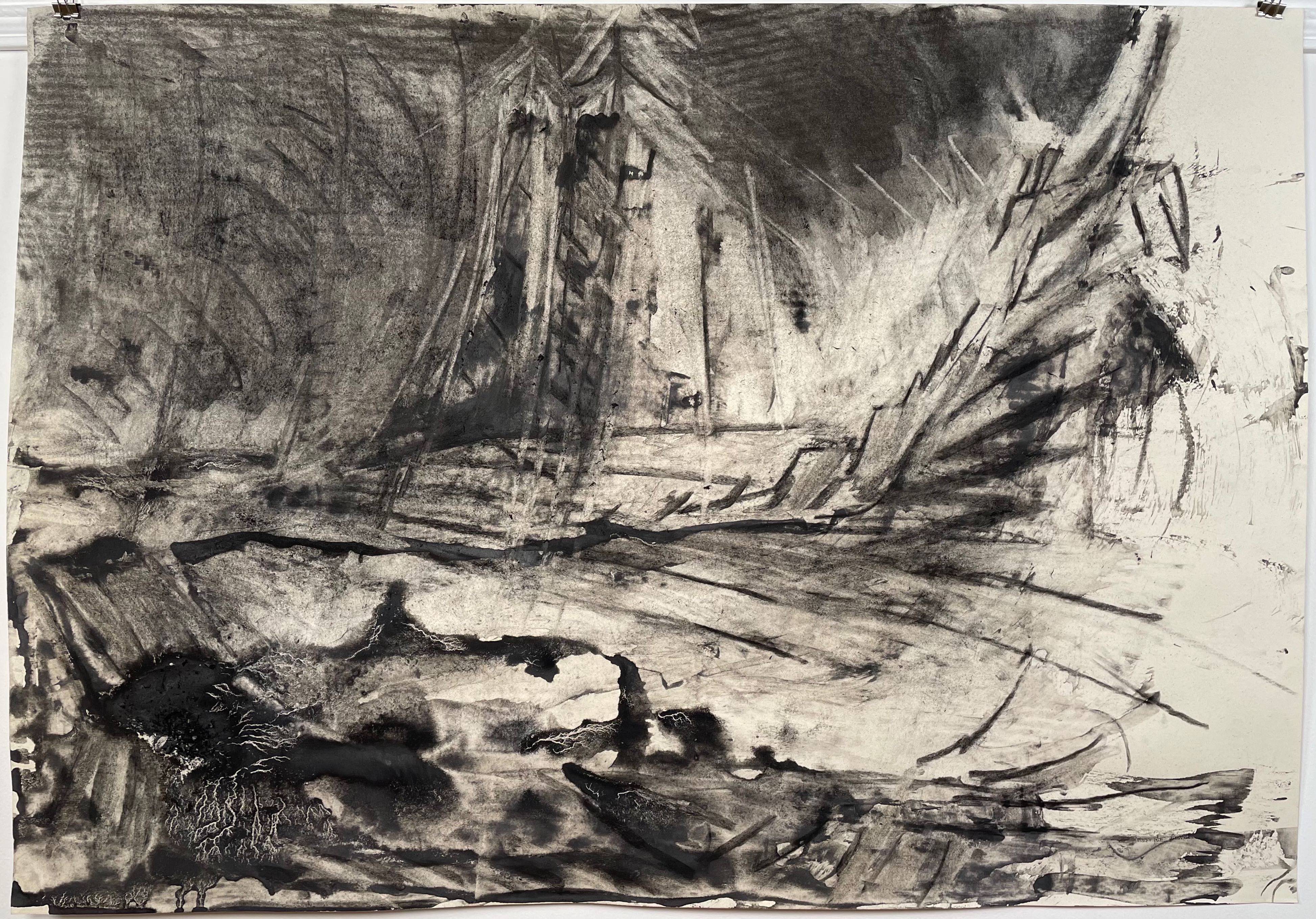

Mono-Pol-Lithic Drawings

The troubling consequences of the pandemic have proven how fragile and vulnerable life on Earth is. My interest in the Anthropocene continues through a new body of work based on the theme of “Mono-pol-lithic”: Monumental-Politics-Lithic. My continued concern in the Anthropocene questions human activities in our existence’s critical zone with ongoing natural resource exploitation as it has transformed our planet’s climate and ecosystem significantly.

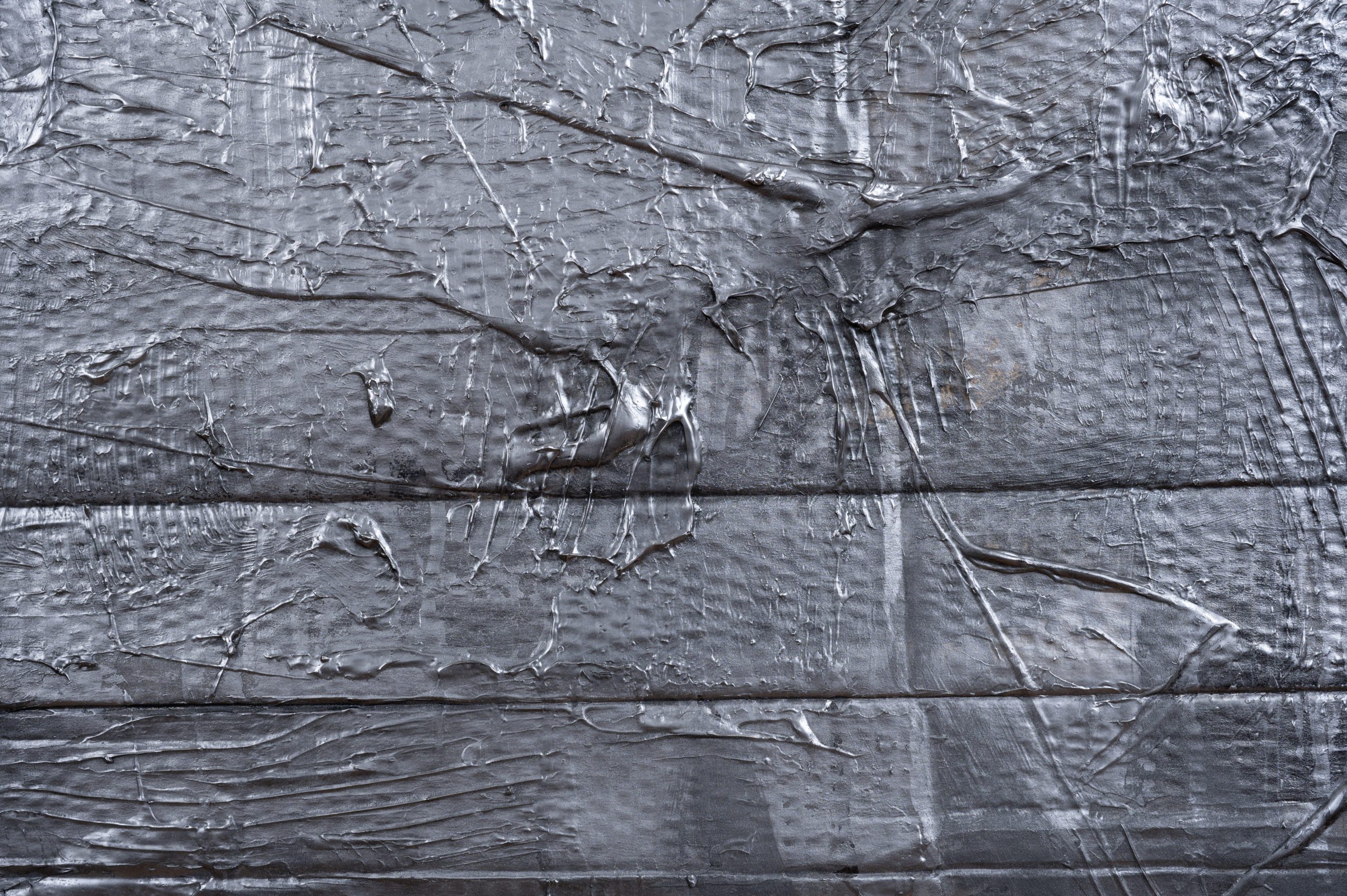

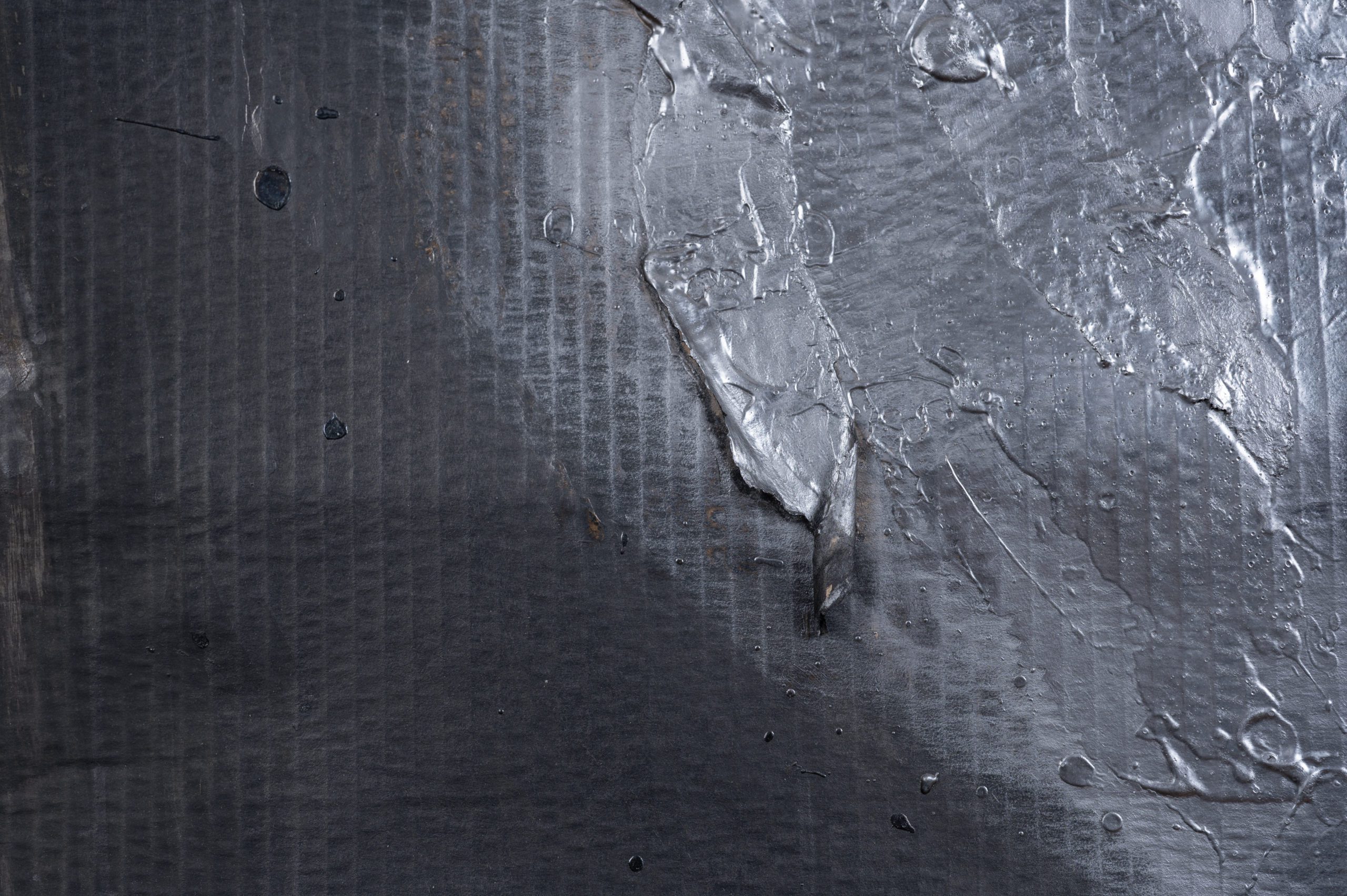

During the pandemic, I focus on relationships between time and acceleration by slowing down through experimental drawing using charcoal, exploring the concept of Mono-Pol-Lithic. I investigate how political agencies have transformed and exhausted the land and how societies and cultures have done the same via manifestations of architecture, enormous structures of power, and massive tectonic activities. Since the Industrial Revolution (the Anthropocene marker) the use, and abuse of nature have accelerated.

My charcoal drawings unfold the moment of paralysis, adopting a traditional tool. Now re-engaging with charcoal, a mysterious, dark, and dusty material connects with my work’s infrastructure forming raw, depleted, and dystopian environments. Charcoal, a material dug out from deep time, generates a massive geologic force into our presence as it was one of the first tools humans used to create artwork.

In times of political and environmental instability, I seek a paradigm shift from economies’ politics towards ecologies’ politics. I want to recall the past, present, and future as interweaving tapestries of my Mono-Pol-Lithic concept. The images are witnesses from the future, which raises questions on shaping the world we inhabit.

Aeaea - Island of Circe, Series of Mnemosyne in the Digital Age

Past work

Gaia Rise: Landscape in an Eroded Field

Katzen Art Center

of the American University Museum, Washington DC

January 25 – March 15 2020

Curated by Laura Roulet

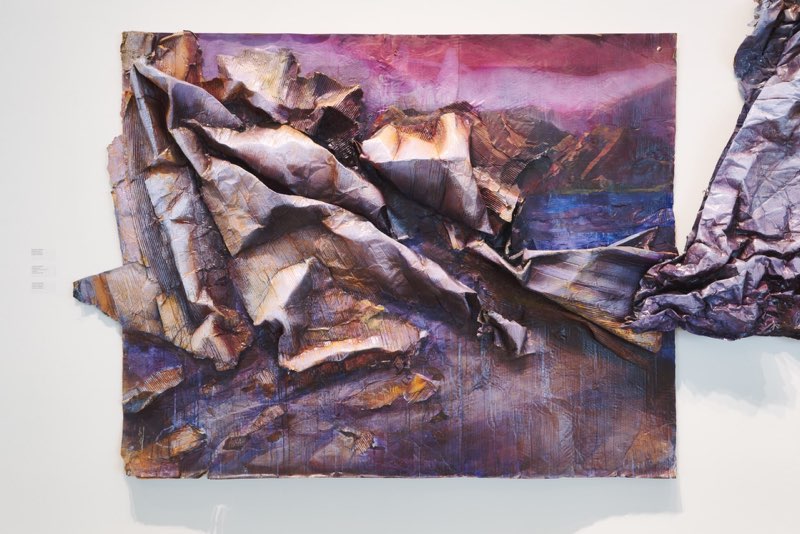

“Artemis Herber is doubly gifted with the Greek heritage of her mother and the German ancestry of her father. Both histories play a key role in the

monumental cycle of painted reliefs created for the AU Museum. Reflecting her deep knowledge of Greek mythology, Germanic landscape tradition, and current environmental theory, Herber combines Western origin stories of mankind and the earth with a contemporary apocalyptic vision. Earth’s steadfast base is now a ravaged, abraded, and degraded beauty. Herber retells the myths of Perseus, Medusa, Poseidon, Persephone, and Odysseus, which form the bedrock of Western culture, updating these classics into newly cautionary parables. Her starting point is the birth of Gaia, Mother Earth, who emerges from a tangled, chaotic nest to rage against human desecration of the planet. Herber’s cyclical themes meld classicism and a revival of eighteenth-century sturm und drang, with a touch of Caspar David Friedrich’s (1774–1840)

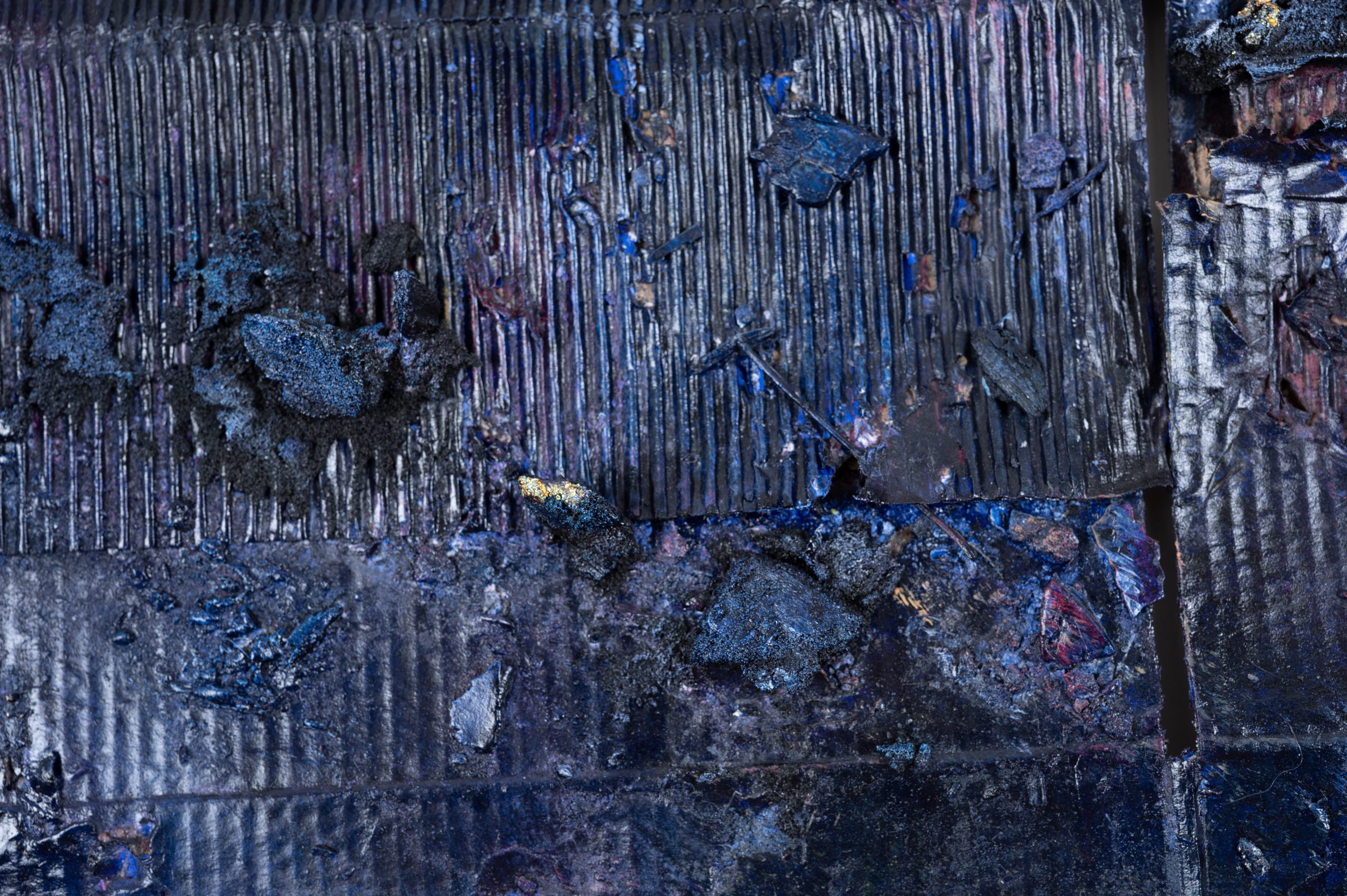

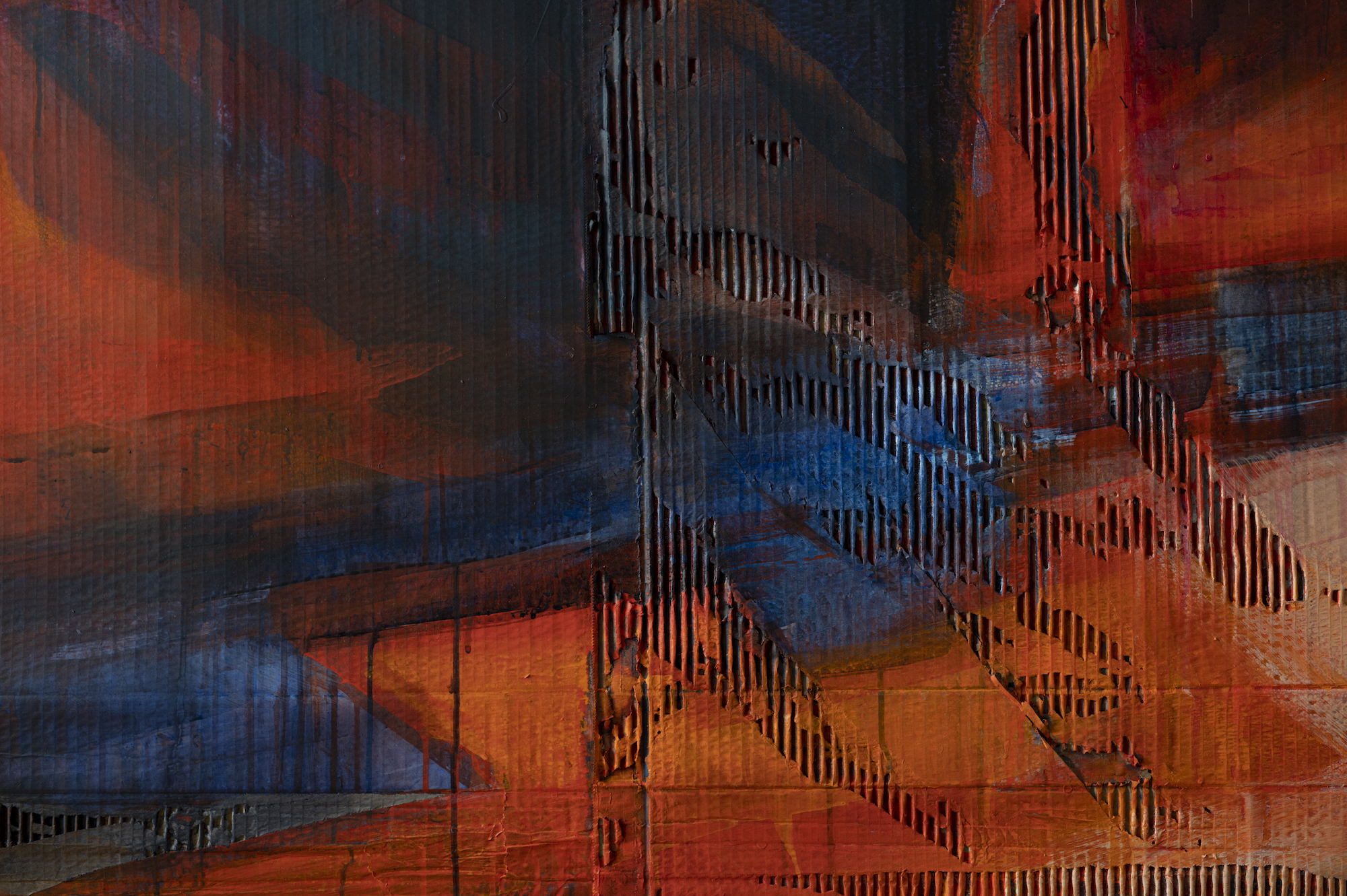

Romanticism blended in. Friedrich’s nineteenth-century landscapes often feature a solitary observer gazing into the sublime depths of nature, a sacred and unknowable space. Time is infinite. The Germanic intertwining of history, culture and nature takes a drastic turn in the twentieth-century painting of Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945), considered the first important post-war artist to grapple with the Nazi past. Herber is clearly inspired by Kiefer’s confluence of history and land-scape. Both work on a spectacular, grand scale, looking both forward and back. While Kiefer employs unconventional materials such as lead and straw, the densely layered surfaces of Herber’s tactile landscapes are built up with dirt, charcoal, and marble dust. Out of ecological consideration, Herber’s “canvas” is recycled, corrugated cardboard. She reuses other materials such as a mop, honeycomb, a woman’s nightgown, all repeatedly wet, wrung out and reassembled. This process, and the curved, enveloping, cyclorama presentation of the paintings, reinforces the theme of tectonic history repeating in an endless cycle of creation and destruction. In Herber’s work, time is mythic and geologic.”

“The politics are global and ecological in “Landscape in an Eroded Field,”… Herber’s myth and history-inspired sculptural paintings on battered cardboard

often depict catastrophe, but stress the force of nature over that of mankind.

Herber’s large pieces, whose rough treatment of cardboard echoes the destructiveness of earthquakes and volcanoes. Sitting on one of the beanbags places

the viewer squarely in the Anthropocene, the era when humanity put itself at the center of the universe.“

Autochthon

Arlington Arts Center VA

Fall Solos, October 13 – December 15 2018

Curated by Blair Murphy

The series of Autochthon points to my interest in Greek mythology and human relationships to geologic forms. In mythology, autochthones are mortals who have sprung directly from the soil, rocks, and trees. In structural geology, an autochthon is a mass of rocks that remain rooted in the foundation it initially formed. This rootedness or sense of place contrasts with the destabilization wrought on the Earth by human activity. I connect the work’s material and conceptual infrastructure with corrugated cardboard, a ubiquitous signature for our globalized consumerism.

‘In her large-scale works made primarily of cardboard, Artemis Herber explores the significance of deep time and the environmental impact of mankind in the Anthropocene. The title of Herber’s SOLOS project, Autochthon, points to her interest in Greek mythology and in human relationships to geologic forms. In mythology, autochthones are mortals who have sprung directly from the soil, rocks, and trees. In structural geology, an autochthon is a large mass of rock

which remains rooted to the foundation rock on which it originally formed. This rootedness or sense of place stands in sharp contrast to the destabilization

wrought on the earth by human activity. Through her use of corrugated cardboard – a ubiquitous signature for our globalized consumerism – Herber

connects the material and conceptual foundations of her work. Herber’s bold creations draw attention to the entanglements between nature, the economy, and environmental degradation, examining the impact of land seizure, exploitation, and large-scale migration on our relationship to the earth.’

“Artemis Herber deals in ancient and even tectonic history in her paintings on shaped, tattered cardboard. The corrugated material once seemed integral to the artist’s rocky landscapes, but these four elegant pieces transcend their packing-box origins”

Erratic Landscapes

McLean Projects for the Arts VA

April 12 – June 2 2018

Curated by Nancy Sausser

Using recycled cardboard, the material used for packing and shipping that is so omnipresent in our consumer society, German-born and Baltimore-based artist Artemis Herber creates intense collaged paintings that explore the complicated interconnections between human beings and the land. In her deep and wide-ranging research, Herber gathers ideas from multiple fields, including philosophy, archeology, economics, and architecture. Of critical interest to her is an investigation of deep time and human impact through the lens of the Anthropocene, which refers to the relatively short period beginning when human activities began to affect the Earth’s ecosystem. Working with a three-point framework that includes land use, time, and global positioning, Herber’s large-scale land and cityscapes employ expressive and energetic drawing and painting techniques and a self-invented torn and cut collage process including both construction and disintegration. Due to their size and dynamic nature, the works create around them an experiential atmosphere, allowing viewers to feel as well as see the ideas Herber is grappling with. While asking the big questions — what characterizes the entanglement between human beings and nature and what impact does our presence on this Earth create — Herber makes art that is equally impactful aesthetically, emotionally, and intellectually.

– Nancy Sausser

In the Galleries: Every picture tells a story, but it’s up to viewers to provide the plot

by Mark Jenkins – May 25 2018

“Baltimore artist Artemis Herber paints on large pieces of found cardboard, integrating the corrugated material’s rips, holes, and other flaws into her finished work. The strategy usually gives Herber’s pictures a sculptural quality, but that’s de-emphasized in “Erratic Landscapes.” In the MPA at Chain Bridge Gallery show, the artist almost metamorphoses into a pure painter.

A close look reveals that the cardboard surfaces are still pitted and torn, which suits Herber’s latest subjects: volcanic scenes in the colors of Earth, stone, and magma. In pictures such as “Polyphemus — After Casting Rocks,” whose centerpiece is a black cave-in, both the landscape and the technique are tectonic and accretive.

The reference to ancient Greek mythology is typical of Herber’s titles. Yet when making this series, the artist was thinking of contemporary events. “Polyphemus” can be seen as “a metaphor about a global refugee crisis,” she wrote in an email. The violence of geology is dwarfed by the brutality of man.”

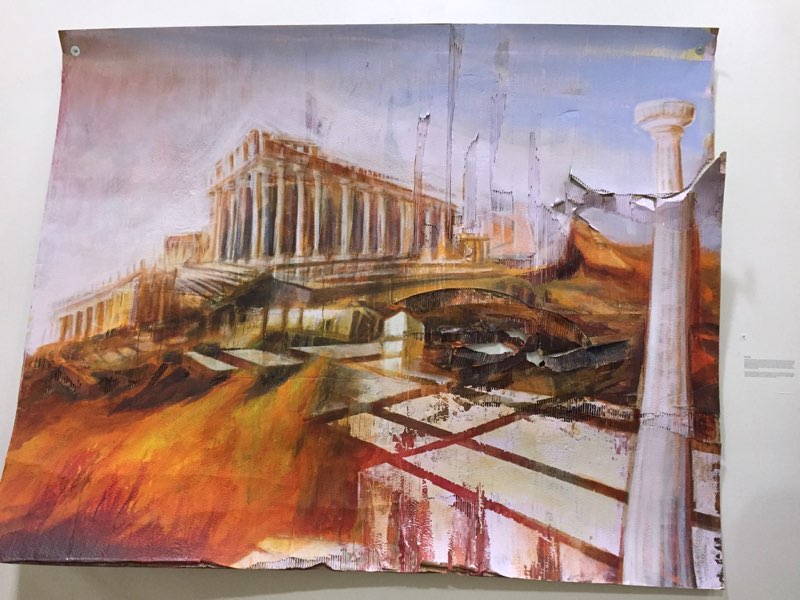

Shifting Identities/ Humanity and Nature

Artemis Herber and Michelle Dickson

King Street Gallery, Montgomery College MD

October 23 – November 2017

Curated by Claudia Rousseau, Ph. D.

Professor, Art History, Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation Arts Center

Although born and educated in Germany, Artemis Herber is also of Greek origin. Her experiences traveling in Greece and in parts of the Middle East, places that are in rapid transition due to environmental and historical changes, had a profound impact on the artist. She is passionate in her concern over the consequences of the Anthropocene, that is, the era of human dominance over the planet, on the natural environment, but also the cultural changes and loss of history this has and continues to affect. An excellent example of the latter would be the destruction of cultural sites, of ancient temples and sacred sites, to make way for new construction and industry. Pollution of the environment is only one result of the loss involved. There is also the loss of memory. Her painting practice of scoring and tearing cardboard boxes parallels her thoughts about these issues. The layering that results from pulling apart the corrugations, a peeling, and rearranging of surfaces, implies the forces of change at work in our world, lost places, and the constant juxtaposition of permanence and impermanence in that environment. She has filled notebooks with texts, with an often-pleading tone, about these effects. “During a time of great uncertainty,” she has written, “humans stand at the threshold between a previous way of life and what their future outcome will become.” Her paintings in this exhibit exemplified this fundamental idea. They are, as she has said, “witnesses…[that] represent the energy of human creativity and the architectural mastery of space” and, at the same time, the opposing negative forces of destruction and degradation.

Despite this, the paintings themselves are rich with color and gesture, as well as varied as to individual subjects represented in each. They are very nearly three-dimensional in some cases, coming forward as much as 10 inches from the wall. Herber works with large brushes, palette knives, and rapid strokes. This dynamic painting process results in exciting compositions that actually draw the viewer to close inspection. They were colorful and strong presences on the white walls of the gallery.

Liminal States

Paintings and Sculptures 2014 – 2017

The Delaplaine Arts Center MD

October 7 – 29 2017

Using corrugated cardboard, an omnipresent raw industrial material used for packing and shipping everything we consume, I raise questions about urban culture and sustainability while exploring geo-economic landscapes expressing local issues on global concerns. Artistic strategies, aesthetics, and themes are liminal by using principles of disappearance, erasure, and disintegration to capture the transitory and reveal the hidden. “Liminal States” examines the continuation of landscapes with a broader perspective through the concept of liminality first described in anthropology by Arnold van Gennep and Victor Turner as a social theory and now conveyed into an artistic vision. My work explores the relationship between space and place with environments permeated with a sense of instability.

Historical, political, and economic environments reflect on generations of cityscapes that seem familiar yet come from another time. They represent the energy of human creativity and the mastery of space, which raises questions on how our will to shape the world will behave at the moment.

(Un)Common Spaces

Spartanburg Art Museum SC

September 15 2016 – January 2017

(Un)common Space (s) is a group exhibition that broadly examines the relationship between natural, constructed, and decaying space. As the health and well-being of our planet continue to decline, viewers are challenged to consider such themes as the loss of natural resources, the lack of interaction between humanity and nature, and the decay of urban landscapes. The works on view range from dynamic urban landscape paintings on non-traditional surfaces to documentary photography and incorporating detritus from abandoned rural sites in mixed-media and encaustic works. These materials and techniques contribute to the visual conversation that balances between permanence and impermanence.

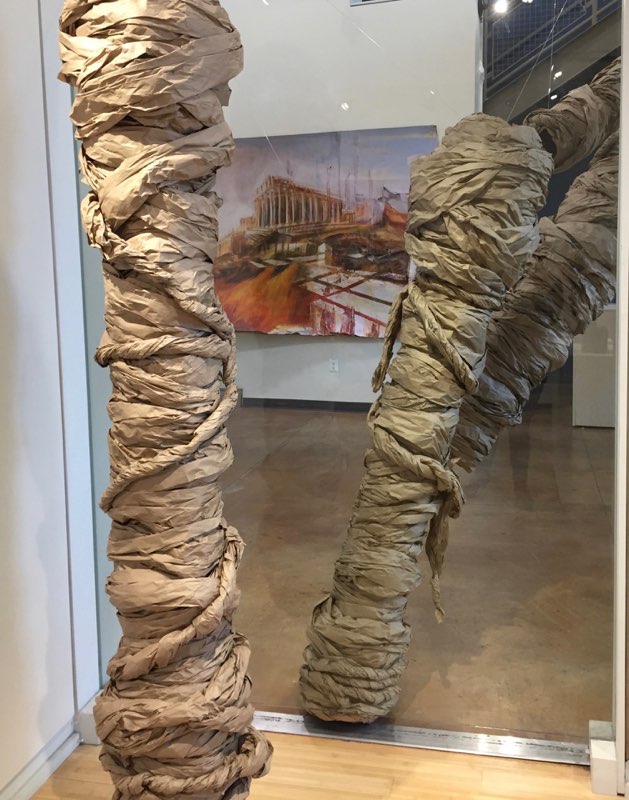

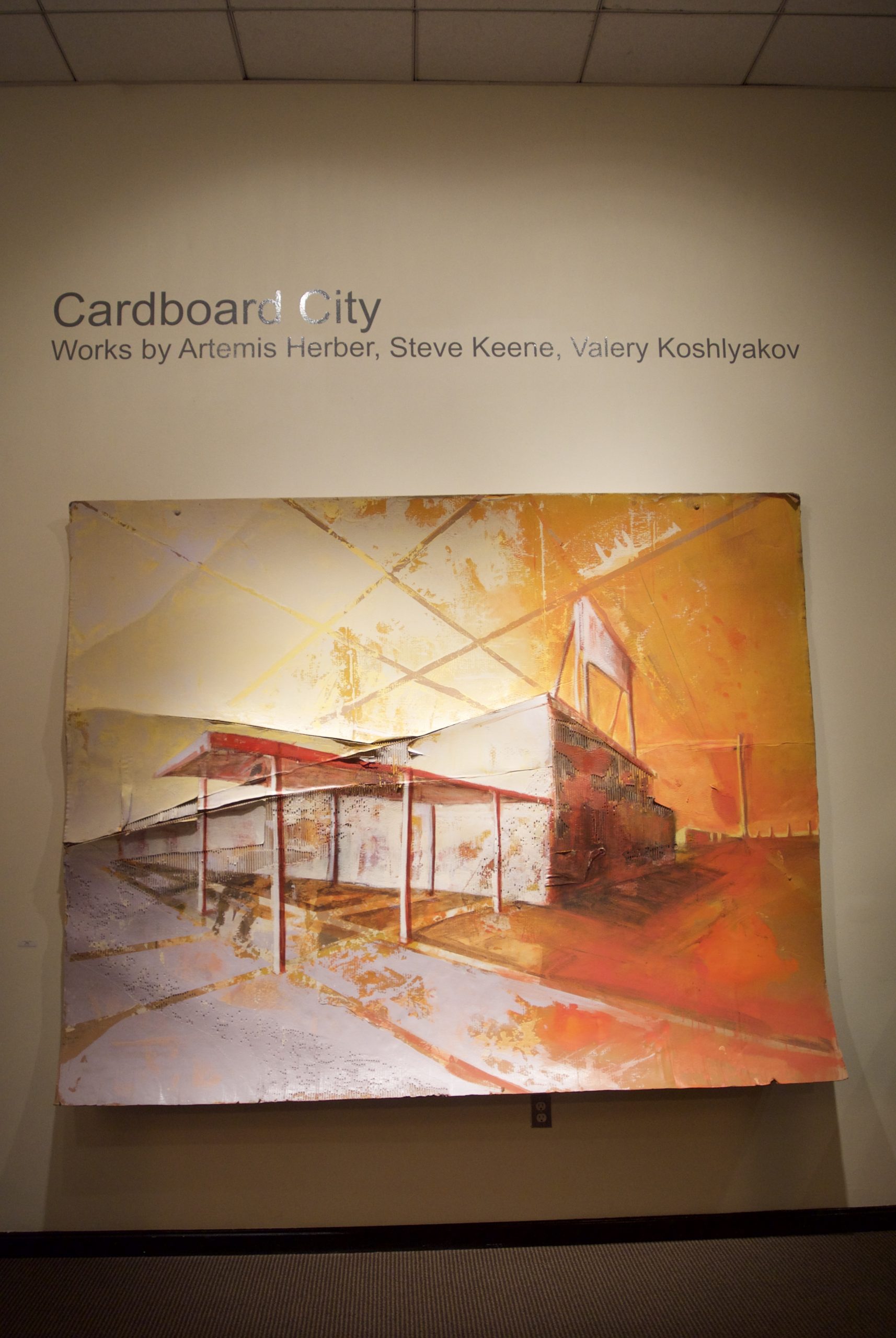

Cardboard City

Goethe-Institut Washington DC

Artemis Herber, Steve Keene, Valery Koshlyakov

August 27 – September 27 2013

What will our cities of today look like tomorrow? What will be left of the monumental architecture and the icons of our mobility and shopping culture? Using cardboard, an omnipresent raw industrial material used for packing and shipping everything we consume, I raise questions about urban culture and sustainability.

In my large-scale paintings, I use the cardboard’s rough, raw aesthetic to invoke themes of urban landscapes and deterioration. Revealing the apparently hidden, I tear and peel cardboard to unveil layers of corrugation, which I integrate into a composition. With its exposed structure of corrugated ridges and its ragged, torn texture, this omnipresent raw industrial packing and shipping material emphasizes the crumbling architecture of industrial constructions. I create a relentless, nearly brutal face of what surrounds us by melding my actions into disruptive gestures generated by the material. The treated cardboard’s aesthetics of rawness and roughness invoke an urban bleakness, environmental desolation, neglect, instability, and destruction. My themes are urban environments empty of humanity and permeated with a sense of instability. I paint cityscapes, forsaken places, and ruined constructions on corrugated cardboard, which I tear, batter, and shape. This ragged canvas captures impressions of locales after storms, disasters, or catastrophes – after the experience of loss of home.

I represent aging, abandoned, crumbling architecture through tears, cuts, and shreds. These techniques provide the basis for motifs of lost spaces, calling to mind a state of bleakness, neglect, and instability of those looking for an orientation homeward in a dehumanized world.

No Man's Land

Arlington Arts Center VA

2014

Curated by Cynthia Connolly

I started with the idea of No Man’s Land when I realized that my paintings capture the impression of recent disasters or catastrophes. Entering No Man’s Land allows me to investigate all places and landscapes shaped by human intrusion.

A dystopian view of our environment raises inevitable questions of what will be left of our lifestyle? What are the consequences of terrestrial demand and intrusion when we transform our landscapes into manufactured environments? And, is there a difference in appearance between a natural and manufactured landscape when human action renders the land uninhabitable?

My paintings imitate abandoned and decrepit places through the application of tears, cuts, and shreds to the surface of the cardboard. This process reveals layers of corrugation, tattered textures, and dissolving surface conditions. I paint the surface of the cardboard in a free manner while being sure to capture the rendition of details. I prefer a rough and raw mode of spills and sketch-like gestures instead of a polished look. I paint with huge brushes and blades to express the spontaneity of action and gestures of my theme. Each of my works is prepared with sensual textures and uneven surfaces so the viewer may explore the material’s full potential. These strategies provide the basis for No Man’s Land motifs, calling to mind a state of bleakness, neglect, and instability in a dehumanized world.